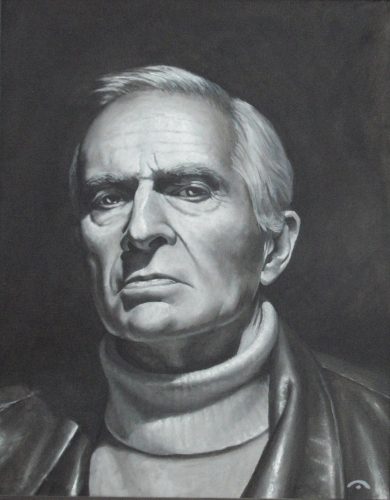

This is a portrait drawn using a prototype version of Tim Jenison’s Vermeer device.

Given my enthusiasm for David Hockney’s controversial book, ‘Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the lost techniques of the Old Masters’, I don’t know why it took me so long, but I recently watched the Penn and Teller documentary, ‘Tim’s Vermeer’.

It’s a fascinating (and, yet again, controversial) investigation into the theory that the Dutch painter, Johannes Vermeer, might have used optics to assist him in achieving his incredible paintings.

To test his theory, US-based inventor and self-proclaimed ‘non-painter’, Tim Jenison, created a full replica of the room that Vermeer portrayed in his painting, ‘The Music Lesson’, together with its contents.

He then went on to develop an arrangement of optical equipment in which an ‘image is projected through the 4-inch lens onto a 7-inch concave mirror on the opposite wall, and then onto the 2-inch-by-4-inch mirror he’d have right in front of his face as he painted.‘

Having discussed the conclusions of this documentary with my venerable portrait sitter, Paul J, he agreed that I could test the theory on a portrait he had commissioned from me of his grandson, Leon.

My prototype was of Tim’s earlier, simplest version of his device, which required a small mirror to be placed at 45 degrees to a vertically fixed (and, ideally, reversed/flipped) image, and a horizontally placed sheet of paper (see second image below).

Lessons learned from this experiment:

- It’s very quick to learn to use;

- It’s possible to use short term visual memory to speed up the drawing time, almost like speed reading whereby you’re scanning three words ahead, whilst processing the last three;

- A first surface mirror is a ‘must’, and can be easily made by removing a makeup mirror from a ‘compact’;

- I’ve also started experimenting with a large ‘flat’ shaving mirror, as I like the larger size, although it also means it’s easier to fog up by breathing on it!

- Positioning the mirror seems to be somewhat by ‘trial and error’;

- It’s easy to knock it and introduce parallax issues, whereby the image in the mirror and on the surface move in relation to each other;

- The image to be copied (if not drawing/painting from life) needs to be reversed. I’d almost finished my first attempt before realising that the lettering I was about to draw was back to front! D’oh!

- I had to scale up my ‘reference image’ to ensure my finished drawing was an appropriate size;

In summary, it was an interesting experiment, and one that I’d like to repeat, especially to test:

- The effect of using the additional optical components in Tim’s final version of the device;

- Testing an observation Hockney made about Ingres (I think) , in which he stated that whilst Ingres may have used optical devices for his pencil portraits, he wouldn’t need to have traced the whole image, just the position of a few key dimensional reference points, such as the position of the eyes, nose and mouth, similar to a facial recognition mapping image;

- Painting from ‘life’ as opposed to from a printed image;

- Painting in colour.

In closing I would say, however, that as an artist I really enjoy the challenge of looking and analysing an object, as well as the ‘trial and error’ of trying to interpret and represent what has been seen, and I quite like seeing the imperfection of the hand and the eye in the finished drawing.

Using optics, whilst effective and accurate, is really rather boring and certainly made me feel like a human photocopy machine, so I wonder if the masters of old would have tried their hardest to keep their reliance of optics to a minimum so that they could spend more of their time using the fun stuff. Paint!!